Adapted from an essay by Scott C. France, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

The trees of a forest are home to a myriad of other plants and animals. Think of squirrels, monkeys, birds, caterpillars, and beetles; bromeliads, vines, lichens, ferns, and bracket fungus. The trees provide a habitat for species that otherwise wouldn’t be there (when is the last time you saw a woodpecker in a meadow?); many species build their nests in the branches of a tree, or, like some woodpeckers, carve out a hole. Some use the branches to hide from predators (think about fox squirrels dashing up into the trees when your dog approaches), while some predators use them as a base of ambush (owls, arboreal snakes, dragonflies, many warblers that pick insects off the leaves or bark) or to capture prey from the air (spiders and their webs). And then of course there are the species that feed directly on the trees, such as voracious tent caterpillars or bark beetles. As scientists we refer to the trees as providing habitat complexity and three-dimensional structure to the ecosystem and in so doing increasing the biodiversity or species richness of the forest.

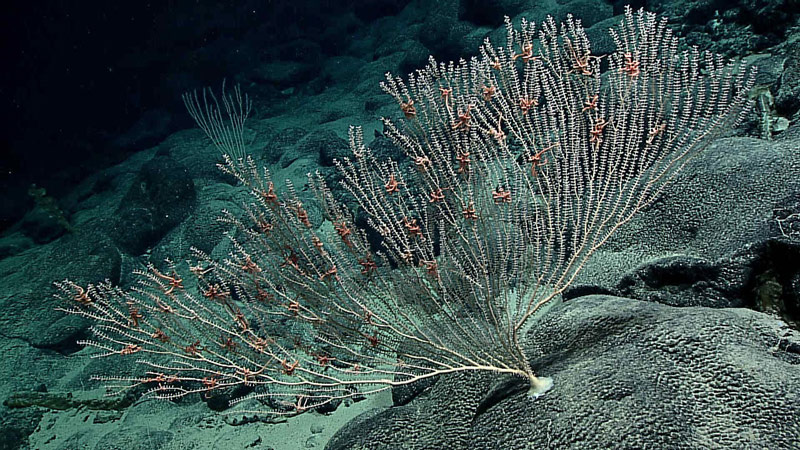

Now consider an octocoral colony and its branches arising above the seafloor. Octocoral colonies provide the same habitat complexity and three-dimensional structure in the deep sea as forests do on land. There are many examples of how octocorals impact local biodiversity. Here are a few.

Suspension Feeders

Like spiders in trees that spin a web in the branches to catch flying prey, there are many animals that climb the branches of corals to capture food that is drifting by in the water column. Among the most common that we see are the brittle stars (Ophiuroidea). There are many different species of brittle stars that can be found on corals, just as there are many species of spiders or warblers in trees. Some of these brittle stars climb up the coral “tree” in order to reach a more rapid current flow, which provides more food per unit of time.

Other animals that use corals as a perch from which to capture drifting food from the water include feather stars (Crinoidea).

General Predators

Like owls and dragonflies that dart from a perch to catch flying prey, or birds that scour the branches for insects, some deep-sea animal predators use coral branches as a base to hunt. A common example are the chirostylid squat lobsters. These crustaceans—neither crab nor lobster but something in between—are evolutionarily adapted to live in the branches of the corals, with hook-like dactyls (claws) at the tips of their back legs used to cling tightly to their host.

Squat lobsters may feed on pelagic jellies and small crustaceans, such as amphipods and mysids, which themselves can be seen crawling over and swimming from the branches of corals in search of a meal.

A different group of brittle stars (Asteroschematidae) from those described above wrap their long, snake-like arms over the branches and may capture small animals that land on the coral, or may feed on the mucus given off by the coral tissue.

Coral Predators

Many animals are attracted to corals as a food source, feeding directly on the polyps. Two examples are corallivorous sea stars (hippasterine asteroids) and sea spiders (Pycnogonida).

The sea stars actually evert one of their two stomachs through their mouth to wrap around the coral polyps, which they then enzymatically dissolve and ingest. They may remain feeding for months on a single coral colony.

The sea spiders insert a muscular proboscis into the polyp and suction out the contents. Other coral predators include solenogasters, which are worm-like molluscs that lack a shell (Aplacophora) and sea urchins.

Home Base

There are many animals that live permanently in the branches of coral colonies, some of them building structures. These include amphipods that build tubes, hydroids, sea anemones, zoanthids, sponges, and barnacles.

A particularly interesting example is a group of scale worms (polynoid polychaetes) that cause the coral to alter its growth to produce small tunnels under the tissue that the worms can live in. Egg-carrying females of some species of shrimp will hang out in coral branches, presumably for protection.

This is just a small sampling of the many animals that benefit from the presence of deep-sea corals. This impact on the overall diversity of the community is one of the reasons we so frequently target areas we think may be rich in corals for exploration.

Further Reading

You can also read “How Octocorals are Like Plants” by Scott France for additional information.